Introduction

Change in organizations is inevitable and happens naturally as organizations adapt to the various forces pulling at the organization, from the outside and from within.

However, most of the changes that take place in organizations are neither intentional nor aligned across the organization, they happen locally as a result of many small choices made by many individuals.

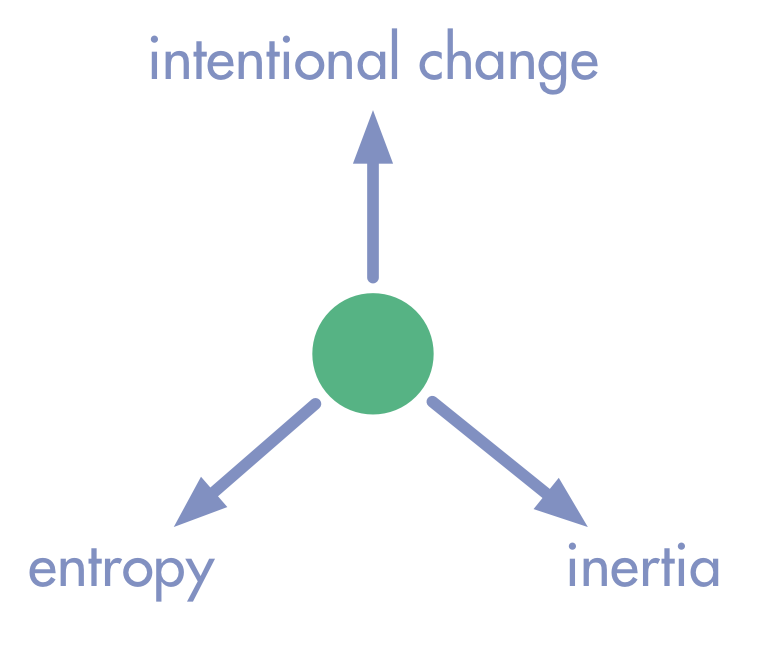

Lots of small and unrelated adaptive changes will lead to giving in to inertia (doing more of the same) and entropy (many independent and unaligned decisions). This is the opposite of intentional change – changing in an organized and aligned way.

All organizations benefit from building capacity for intentional change in order to become and remain effective.

This paper presents a simple model for mapping influence of internal and external forces to organizations, identifying motive for change and delegating accountability for plotting a course of action, and finally incrementally implementing the resulting change.

A shared model for change in organizations

Change – adaptive or intentional?

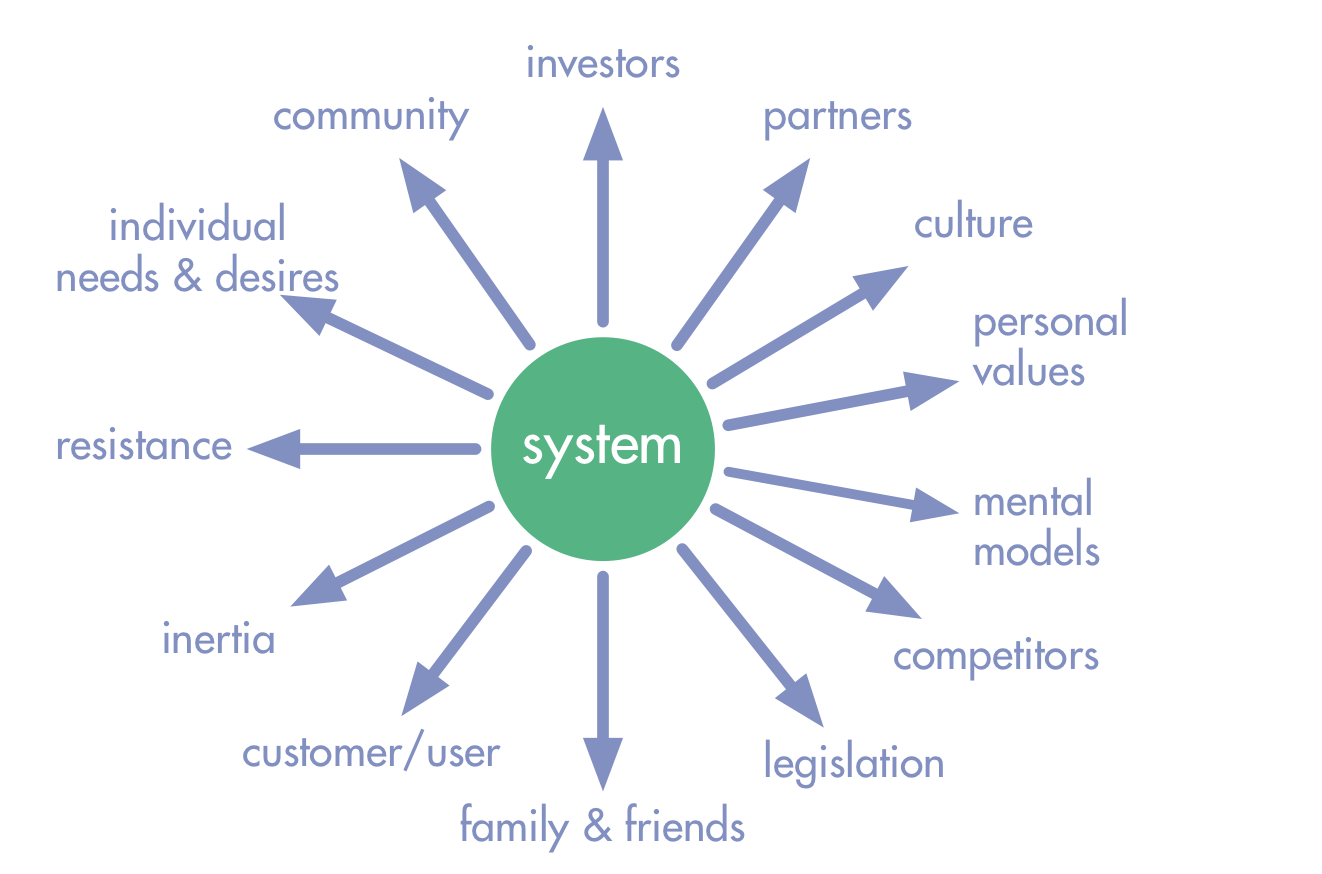

A change is anything happening in the (outside) world, or in our heads (our model of the world) that affects the working of an organization, usually as a result of one or more external or internal forces pulling at an organization.

For many organization, most of the change they undergo is adaptive change – continuous change of a system as the result of its members individually reacting to the pull of internal and external forces.

Adaptive change has two main sources: inertia and entropy. Inertia is the result of people doing things they way they’re used to doing them, the combined effect of individual habits and organizational culture which keeps an organizations moving into a certain direction. Entropy is the result of individual and unaligned responses to a problem or challenge, this introduces an element of randomness to an organization’s operation. The sum of countless small local fixes and patches to an organization’s behavior has a substantial effect on the organization as a whole.

Intentional change in a system happens when all members affected by change understand context and motivation, agree on direction, and collaborate on change.

It’s an enormous effort to intentionally change an organization, and in many organizations big change initiatives are not particularly successful.

A large intentional change needs to be aligned across an organizations, so it’s essential for success that all members of an organization are both enabled and empowered to effectively contribute to and collaborate on that change. To that end, members do not only need to understand motive and nature of the intended change, they also greatly benefit from sharing a common model for thinking about organizations1 and working with change.

The more members share same mental models about organizations and change, the greater is an organization’s capacity for intentional change.

Organizations

An organization is any group of people organized for a particular purpose and around a shared motive (see [Drivers – a systems perspective][]). This may a band of three kids rehearsing in a garage, or a multinational enterprise.

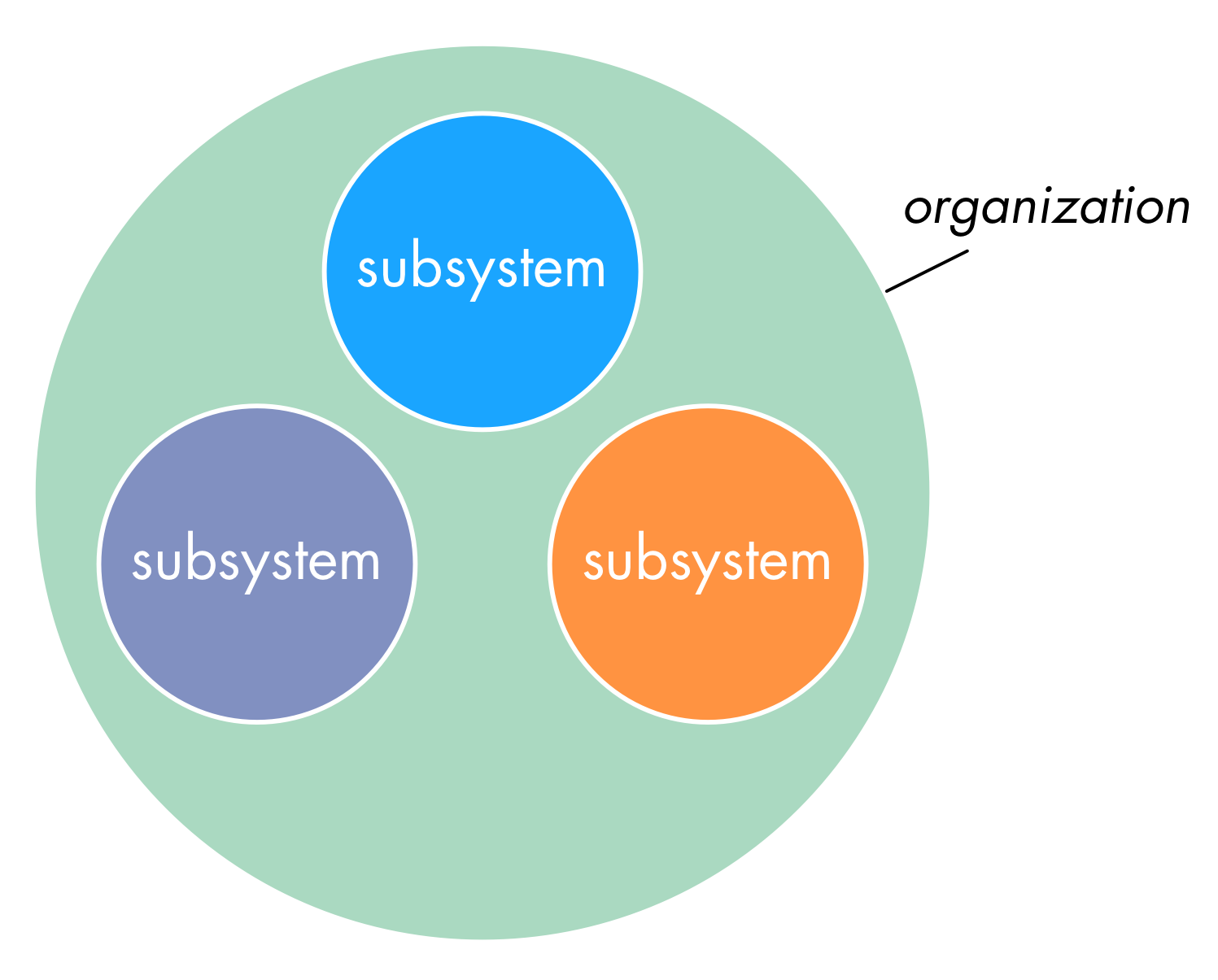

Any organization is a human system, i.e. a network of individuals or of circles (or groups) of individuals. Human systems are interdependent and may overlap, i.e. they may share members with other systems. Often a human system contains subsystems, which are again interdependent and potentially overlapping, e.g. in an organization there are departments, units, teams, tribes, or communities of practices. A special case of a subsystem is a role.

Whether or not an organization is effective depends on how well the members of the organization are able to “organize” or orchestrate their collaboration towards the organization’s purpose, i.e. the members’ capacity of both making good agreements, and of fulfilling them.

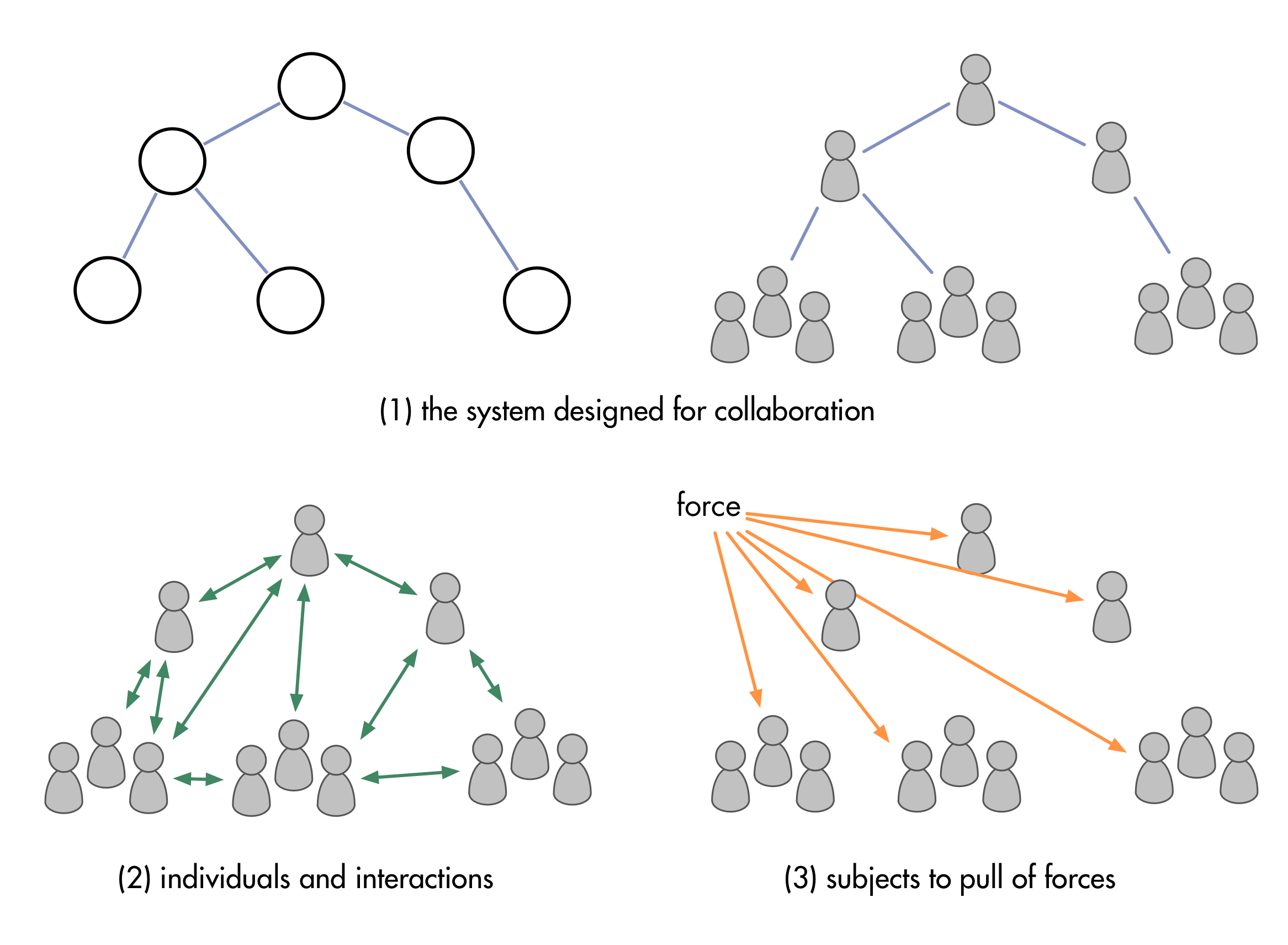

In order to understand how organizations operate and change over time it’s helpful to consider three specific aspects of an organization:

- the system designed for collaboration: an organization can be viewed as the the body of all agreements about collaboration, including the structure of departments, teams and roles created for collaboration within the domain of the organization, and the agreed upon connections and interactions between them.

- the flow of value: the networks of individual members of the organization and their interactions while actually contributing to the flow of value (within the domain of the organization), including but not limited to “official” projects and “unofficial” collaboration

- a system of subjects to forces: a network of groups or individuals subject to various forces pulling at the organization, and responding to that pull.

Many organizations invest a lot of time in maintaining organizational structure and procedures which are not particularly helpful for the flow of value. In an effective organization the system for collaboration is created in alignment to the forces pulling at the organization, which results in the system being mostly identical to the actual network of individuals and their interactions, i.e. the org chart mirrors what is actually happening, and both value and information flow as intended. In this state, an organizations members are doing their best to adhere to the system for collaboration, and evolve the system as soon as they see it’s no longer fit for purpose.

Tension, forces and pull

An organization, as any human system, is subject to the pull of various forces which attempt to change the system.

Tension is the effect of multiple forces simultaneously pulling at a system. Tension often manifests itself as uncertainty: challenges, problems, risk or opportunities.

A tension can be understood and explained in terms of forces pulling at the system itself or a subsystem, within a certain context (e.g. explained through specific conditions or actors).

A force is any influence with the perceived ability to influence an organization. Forces may be needs of individuals within the system, needs of the system itself (or of a subsystem), or external forces (which may, again, be needs of individuals or other systems).

| Examples for external forces pulling at organizations |

|---|

| pull of market and competitors |

| compliance to regulation or legislation |

| requirement of customers and user need |

| needs of the environment |

| needs of member’s families and communities |

| needs of the community around an organization |

| Examples for internal forces pulling at organizations |

|---|

| organizational culture (shared assumptions or chosen values) |

| members’ needs (shared or individual)2 |

| individual member’s values and mental models |

| entropy (local and unaligned responses to tension) |

| inertia |

An organization’s members experience symptoms or effects of tension, and sometimes the subjective experience of a tension turns out to be a misconception. The tension itself, however, is not merely a subjective experience, the forces at play may very well be strong enough to destroy an organization.

There’s two possible responses to pull: individually adapting to pull (adaptive change), or collaborating on discovering motive and then an orchestrating an appropriate response (intentional change).

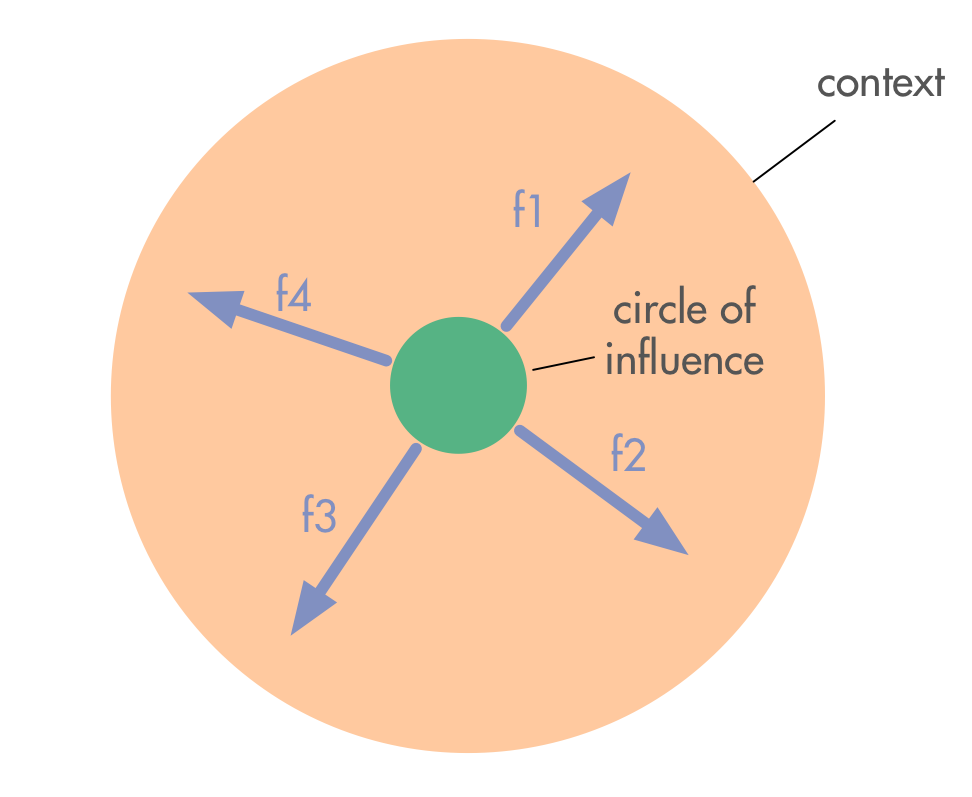

Each force has a circle of influence – the members of an organization who are directly affected by the pull.

Identifying the root cause: Often what is perceived as a tension can be revealed to be only a symptom of another tension, the forces at play merely being symptoms or consequences of other forces. In that case the circle of influence is just part of a much larger circle. It’s essential to try and discover the root cause of a tension, otherwise it may be impossible to respond to that tension effectively. One indicator for organizations dealing with symptoms instead of root causes is similar tensions appearing again and again across the organization.

Drivers – a systems perspective

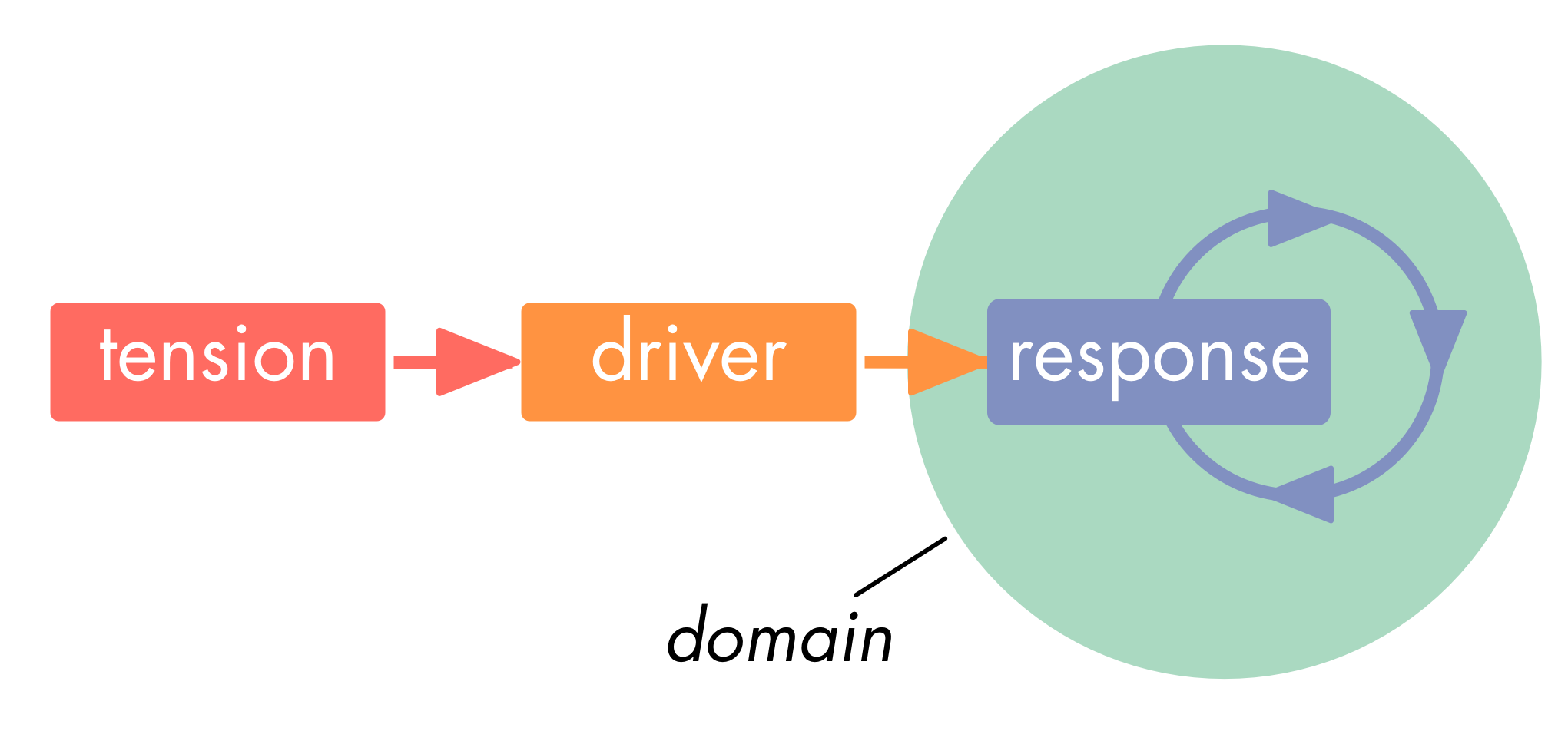

A driver for an organization or one of its subsystems is the motive why the system would want to respond to a specific tension. Being clear about the driver helps determine what constitutes an adequate response to a tension.

Drivers can be argued, i.e. for each driver there’s reasons why a system would respond to a tension – the needs3 or requirements of a system to resolve tension (“this is a driver because…”).

The primary driver of a (sub-)system is the motive why this system has been created in the first place. There is a primary driver for an organization, and and a primary driver for each of its subsystem. All drivers within an organization must be aligned to the primary driver of the organization itself, and to all drivers it is nested within.

Organizational drivers are best described as the combination of a tension and the motive to respond. Sometimes the tension is obvious or implicit. Since each driver only exists in relationship to a specific tension, if the tension is resolved, the driver also ceases to exist.

|Relationships of drivers ||

| Relationship | Explanation |

|---|---|

| nested | the subdriver is a consequence or symptom of the superdriver |

| compound | one driver is a combination or a set of several other drivers |

| independent | independent drivers are unrelated |

| (inter-)dependent | drivers that influence each other, but are not necessarily nested |

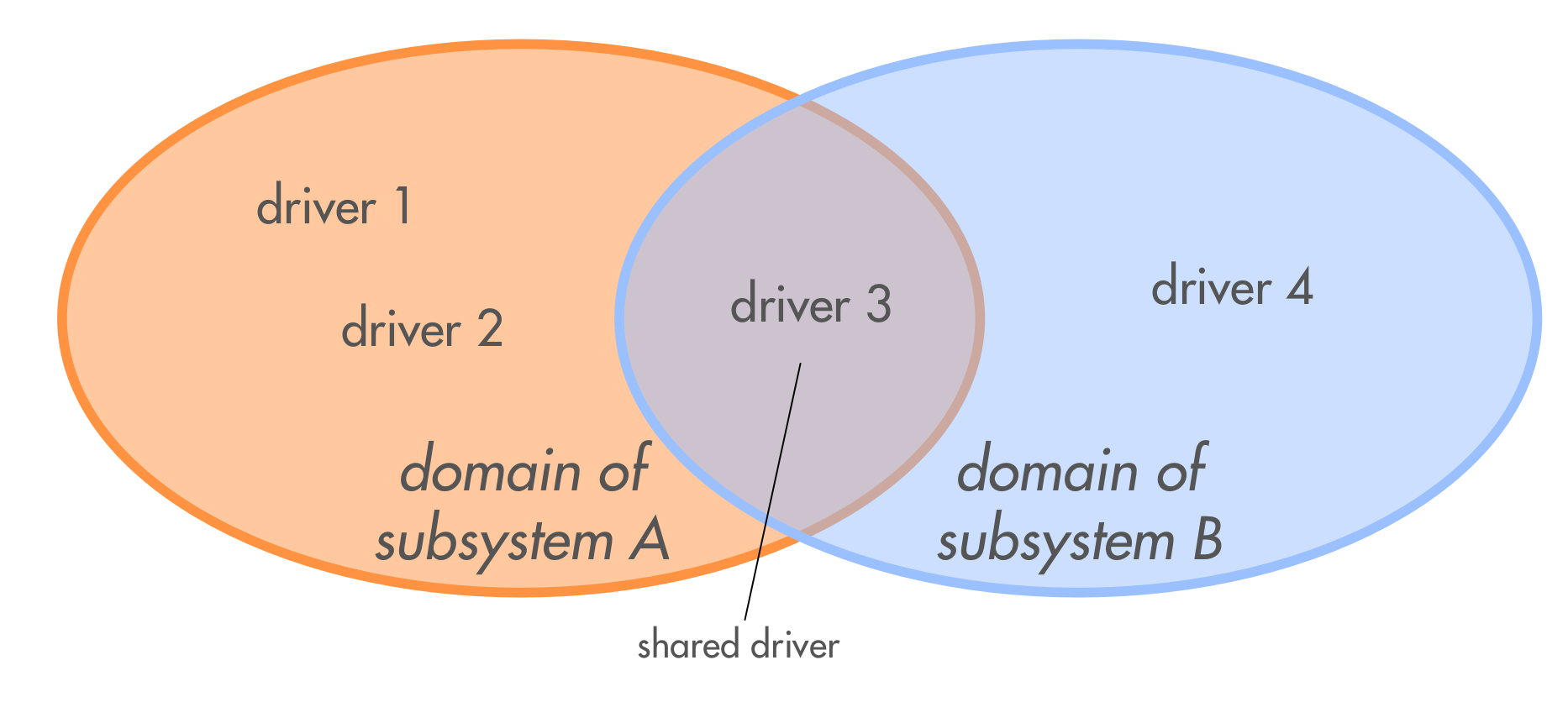

| shared drivers | drivers that are shared between two or more systems, e.g. along a value chain |

Domains of organizations

A domain45 is the area of (semi-)autonomy and accountability of a an organization or one of it’s subsystems (i.e. a circle or a role) in response to its primary driver. In other words, it’s the sphere of activity and concern of a system, the area (or field) of work the system is accountable for.

The domain of the organization is the area of concern of the entire organization, which is defined and agreed upon in relation to the organization’s primary driver.

The whole organization, and each of its subsystems – circles and roles – have their distinct domains. Each domain benefits from clear boundaries and requires the capacity for effective response to its primary driver.

The level of autonomy of a subsystem is a consequence of the relationship of the subsystem’s domain to that of other subsystems: Domains may be nested within each other (a subdomain inside a superdomain, e.g. one development team in a development unit), independent from one another (e.g. an organizations’s cleaning services and IT services), or interdependent. i.e. overlapping, but not nested.

Evolving organizations

Here’s a simple model how organizations can intentionally address tensions within area of concern: by first determining the motive to respond, and then delegating the response to (semi-)autonomous subsystems.

Many of the new drivers that are discovered in an organization fall into an existing domain and thus are simply addressed by the corresponding subsystem. This is part of the normal operation of any organization. But sometimes an emerging driver can’t be addressed effectively by the present organizational structure, so the organization needs to evolve to respond to that driver by either adapting the domains of existing subsystems, or through creation of a new one.

- Creating a new subsystem: The new driver becomes the primary driver for the new subsystem, and a new domain is defined, which needs to allow for an effective response to the driver without creating unnecessary side-effects6, so it also should take into account existing subsystems and their domains.

- Adapting existing subsystems: Sometimes the simplest way to respond to a new driver is by extending an existing domain – the previous primary driver and the new driver becoming a compound driver for the corresponding subsystems. Other possibilities include moving shared services into a dedicated subsystem, or adding more capacity to a function by turning a role into a circle.

From tension to intentional change

Let’s now take a closer look at what needs to happen to develop an organization by intentionally responding to tensions within the organization’s domain.

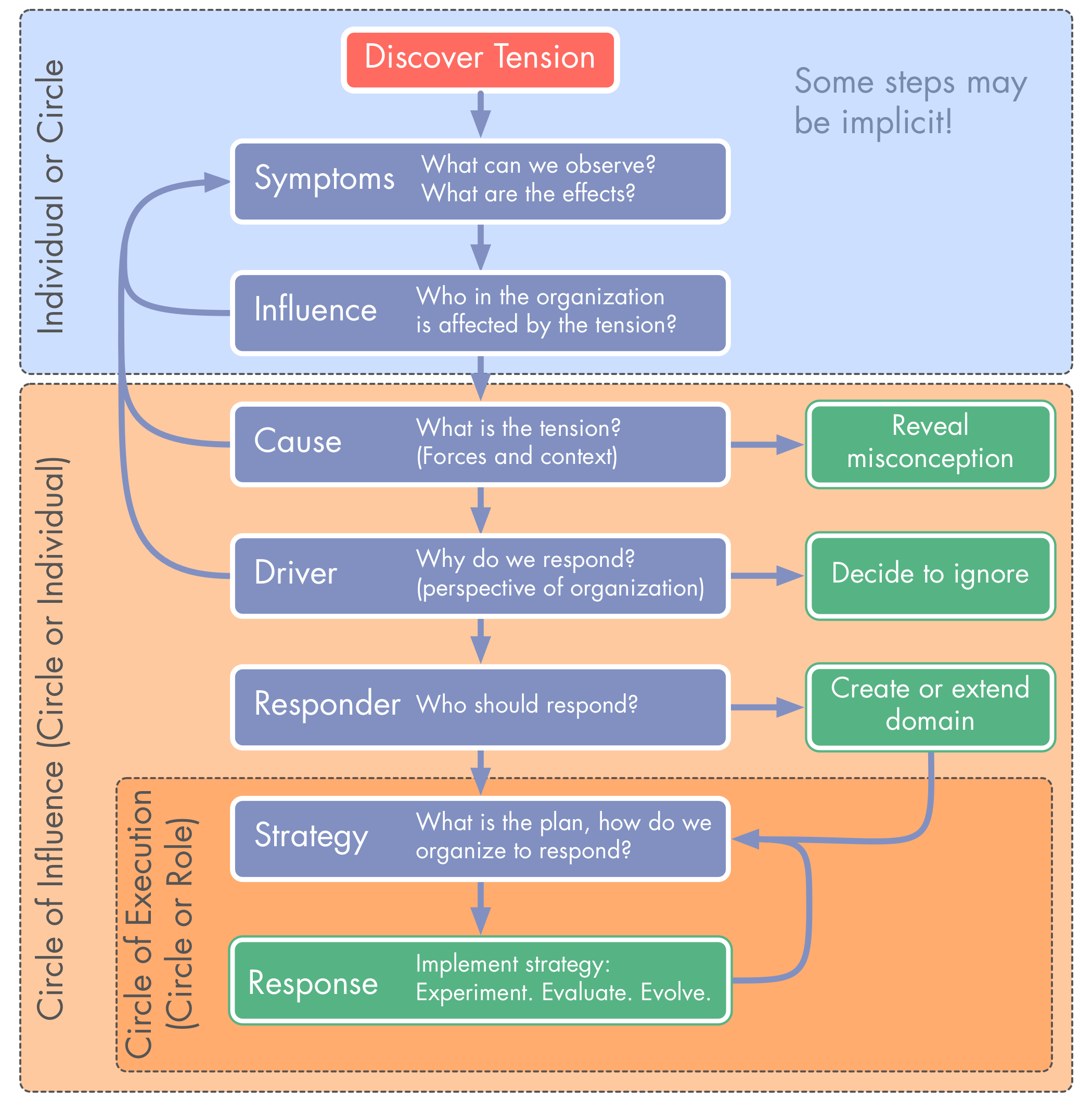

Here’s a map of all the steps that need to be taken from the discovery of a tension to taking action. Some steps may be implicit, and often steps are re-visited as new information emerges.

Steps 1 and 2 are taken by the individual or circle discovering the tension, steps 3-5 take place in the circle of influence of a tension, and 6-8 are handled in the circle of execution the response is delegated to, which is a subset of the circle of influence.

Symptoms

What can we observe? What are the effects?

Symptoms of a tension may be noticed by an individual, or discovered by a group, e.g. in retrospectives, stand-ups, governance meetings, or any other meeting.

The first step is listing symptoms, the observable effects of a tensions, which will help identify where a tensions needs to be processed. These symptoms will later be used by the circle of influence for discovering and understanding the actual tension.

Influence

Who in the organization is affected by the tension?

All the people inside the organization affected by a tension form the circle of influence of that tension.

The circle of influence is accountable for:

- understanding the tension or revealing the misconception

- identifying the driver to respond to the tension

- delegating the response

- the outcome of the response

Sometimes, e.g. when a tension affects an entire organization, the circle of influence is very large, so the act of navigation can (and should) be delegated to a subset of that circle.

Often it’s clear who is affected by a tension by looking at the symptoms, however, sometimes it may be necessary to first identify the forces at play (see step 3).

After the circle of influence has been identified, the tension is taken to circle of influence to make the decision whether or not to respond, and where to delegate the response to. If the circle of influence is a permanent circle, the tension may simply be added as an agenda item for the governance meeting. Otherwise a dedicated meeting or workshop for processing the tension needs to be scheduled.

Cause

What is the tension? (Forces and context)

In order of determine whether or not to respond to a tension, and who is needed for responding effectively, the circle of influence first needs to understand the tension and identify its source, or root cause.

The following questions generate insights relevant to understanding a tension as a system of forces in a certain context:

- What are the different forces?

- What are they pulling at?

- What is the cause of these forces?

- Who are the actors involved?

- What are the relevant conditions?

- Who is affected by the tension?

Often in this step a circle reveals misconceptions about the tension, its forces, symptoms or its root cause.

Driver

Why do we respond?

The driver describes the motive for responding to the tension, it is explained and argued form the perspective of the organization or one of its subsystems in relation to the effects/symptoms of the tension at hand.

The circle of influence may decide to ignore the tension, or defer it for later review, e.g. by scheduling a follow-up meeting with the entire circle, or delegating accountability for the review to a role or circle.

Ignoring or deferring the tension may result in adaptive change.

Responder

Who should respond?

After the driver is understood, the next step is delegating accountability to respond to the driver and resolve the tension.

The driver is delegated to the circle of execution7. This is either an existing subsystem if (a) a tension is clearly inside the domain of that subsystem, or (b) it appears reasonable to extend the domain of that subsystem. Otherwise a new subsystem is created to respond the the driver.

If delegation is not a straightforward process, the circle of influence can create a (temporary) role or circle with the function to assess the situation, propose a course of action to the circle of influence, and, if necessary, oversee the creation of a new subsystem8.

When delegating to an existing subsystem, sometimes it’s necessary to extend the capacity of that subsystem, e.g. by adding new members to a circle, training people for new skills, or adding more monthly hours to a role. Creating a new domain increases complexity of the organization and may subsequently lead to additional tensions.

To identify the circle of execution, ask the following questions:

- Where can we respond effectively?

- What knowledge, resources and skills are required?

The circle of execution7 is those the response to the tension is delegated to, they extend the circle of influence, because they are affected by the tension when they work on on resolving it.

The circle of influence is accountable for both the delegation, and for the outcome (i.e. the result of the delegation). This implies that circle of execution needs to be transparent to the circle of influence so progress can be observed.

Strategy

What is the plan, and how do we organize to respond?

For a new subsystem, or for a driver that requires a non-obvious response, it is helpful to outline a strategy, i.e. the general approach of the response, which is then implemented and refined along the way.

The strategy is co-created by the circle of execution, e.g. through proposal forming, in a kickoff workshop, or any creative format that seems appropriate, and subsequently reported back to the circle of influence.

A strategy explains the form of the response, the outline of a plan, and the intended outcome to evaluate the strategy against, as well as a list of essential agreements about collaboration (guidelines, methods used etc.) to successfully implement the strategy. For an existing circle or role, the strategy might include amendments to existing agreements.

| Various forms of responses to a tension |

|---|

| a single task |

| change or update of existing strategy or agreement |

| guideline or plan for collaboration |

| project (a series of tasks and an intended outcome) |

| product (result or goods created |

| service (assistance, continuously or on demand) |

The strategy needs to be just good enough to get started and run safely, depending on the driver, it explains either how to respond to the driver, or how to go about identifying the appropriate response.

In the first case the strategy may be a rough explanation of a guideline or task, the outline and intended outcome of a project or a high-level description of a product or service.

In the second case the strategy might contain a plan how to identify the appropriate response, a workshop format, research to be completed, and criteria for a successful outcome.

Response

Experiment. Evaluate. Evolve.

An effective response to a tension needs at least to reduce effects of tension, or resolve the tension altogether. Especially for the more complex or challenging tensions – those where intentional change will bring the greatest benefit for an organization – an effective response cannot be designed beforehand, as it is not clear from the beginning how the organization itself and its environment would react to the planned response.

Therefore, identifying and implementing an effective response is an iterative and empirical process. It’s best to consider the response to a tension as an experiment, to evaluate the outcome and then update the experiment with what has been learned. As more information becomes available, it will also sometimes be necessary to update the strategy.

But this incremental approach is also helpful for many other decisions an organization or one of its subsystems is facing. It prevents analysis paralysis and instead empowers the members of an organization to embrace change and create a learning organization.

Closing

When all members of an organization share the same mental model for developing the organization, it’s so much easier to communicate where the organization should go, and how to best collaborate on taking it there together. Growing an organization is hard, but speaking the same language is a great first step for making it happen.

This model for intentional change in organizations builds on Sociocracy 3.0 (S3), a framework of more than 60 patterns for evolving agile organizations. You will find many helpful resources about S3 at http://sociocracy30.org.

- and especially about organizational structure and the way organizations develop and grow ↩

- e.g. need for autonomy, mastery, purpose, relatedness, security or happiness ↩

- To clarify the relationship of individual needs and the needs of the system: The needs of individuals may be forces contributing to a tension, but the system might have a motive to satisfy the needs of an individual in order to enable or sustain the individual’s contribution to the organization. ↩

- In the context of an agreement, we refer to the scope of the agreement, rather than the “domain” ↩

- In this context, domain is used only in the meanings of “sphere of activity, concern, or function, field”, and “sphere of influence”. It does neither refer to a part of an organization (i.e. a department, resort or team), a field of knowledge, the expertise or interest of a person, or a distinctive group of people with some shared interest. ↩

- Since each new subsystem adds complexity to an organization, it brings the potential of tension with existing subsystems, e.g. a conflict over resources, or the need for coordination. ↩

- the circle of execution may be only one person ↩ ↩

- e.g. finding or recruiting members for a circle, facilitation of selection to a role etc. ↩